- バックアップ一覧

- 差分 を表示

- 現在との差分 を表示

- ソース を表示

- 2.Fortran90/95入門 へ行く。

- 1 (2010-02-18 (木) 11:44:32)

- 2 (2010-04-28 (水) 13:49:35)

- 3 (2010-04-28 (水) 20:21:00)

- 4 (2010-04-29 (木) 11:35:26)

- 5 (2010-04-29 (木) 14:28:23)

- 6 (2010-04-29 (木) 15:56:35)

- 7 (2010-04-29 (木) 21:16:08)

- 8 (2010-04-29 (木) 22:01:29)

- 9 (2010-05-06 (木) 01:00:15)

- 10 (2010-05-06 (木) 07:28:58)

- 11 (2010-05-13 (木) 01:55:31)

- 12 (2011-04-21 (木) 10:33:42)

- 13 (2011-04-23 (土) 13:11:31)

- 14 (2011-04-24 (日) 01:28:15)

- 15 (2011-04-25 (月) 12:30:19)

- 16 (2011-04-25 (月) 16:56:44)

- 17 (2011-04-28 (木) 12:56:56)

- 18 (2011-04-28 (木) 14:59:30)

- 19 (2011-04-28 (木) 18:34:48)

- 20 (2011-04-29 (金) 22:44:11)

- 21 (2011-05-03 (火) 18:15:14)

- 22 (2011-05-10 (火) 11:44:17)

- 23 (2011-05-10 (火) 13:41:13)

- 24 (2011-05-10 (火) 18:20:46)

- 25 (2011-05-12 (木) 11:46:11)

- 26 (2011-05-12 (木) 14:03:43)

- 27 (2011-05-12 (木) 20:16:42)

- 28 (2011-05-13 (金) 12:26:16)

- 29 (2011-05-13 (金) 20:00:28)

- 30 (2011-05-14 (土) 18:54:29)

- 31 (2011-05-19 (木) 15:02:16)

- 32 (2011-05-31 (火) 12:52:54)

- 33 (2011-06-09 (木) 19:11:14)

- 34 (2011-06-23 (木) 10:23:26)

- 35 (2011-08-06 (土) 15:17:00)

- 36 (2011-09-13 (火) 13:46:23)

- 37 (2011-10-31 (月) 15:30:36)

- 38 (2011-12-31 (土) 09:56:43)

- 39 (2012-04-11 (水) 14:32:14)

- 40 (2012-04-25 (水) 21:44:49)

- 41 (2012-04-26 (木) 12:37:57)

- 42 (2012-04-26 (木) 14:39:05)

- 43 (2012-04-26 (木) 23:09:18)

- 44 (2012-04-27 (金) 12:22:10)

- 45 (2012-04-27 (金) 16:30:01)

- 46 (2012-05-09 (水) 19:29:23)

- 47 (2012-05-10 (木) 10:34:51)

- 48 (2012-05-10 (木) 16:07:13)

- 49 (2012-05-10 (木) 19:56:13)

- 50 (2012-05-11 (金) 11:32:33)

- 51 (2012-05-11 (金) 17:17:40)

- 52 (2012-05-17 (木) 09:11:29)

- 53 (2012-06-02 (土) 01:24:38)

- 54 (2012-12-23 (日) 16:57:53)

- 55 (2013-04-26 (金) 00:50:53)

- 56 (2013-04-26 (金) 13:51:21)

- 57 (2013-05-02 (木) 14:50:44)

- 58 (2013-05-03 (金) 18:04:08)

- 59 (2013-05-07 (火) 11:01:27)

- 60 (2013-05-08 (水) 13:47:26)

- 61 (2013-05-09 (木) 11:32:36)

- 62 (2013-05-09 (木) 17:03:05)

- 63 (2013-05-13 (月) 12:25:26)

- 64 (2013-05-15 (水) 12:04:47)

- 65 (2013-05-16 (木) 14:38:35)

- 66 (2013-05-16 (木) 22:17:54)

- 67 (2013-05-27 (月) 11:47:34)

- 68 (2013-05-30 (木) 14:50:58)

- 69 (2013-06-06 (木) 14:33:09)

- 70 (2013-06-12 (水) 11:34:19)

- 担当教員

- 演習日

- はじめに

- エディタとコンパイラ

- Fortran90/95の歴史

- なぜFortran90/95か?

- Fortran Legacy

- 定番、hello, world プログラム

- 【演習】

- サンプルコードによるFortran90/95入門

- 【演習】

- Fortran90/95に対する誤解

- 実際的なサンプルコード

- Fortran90/95の特徴

- C言語と極端に差がつく例

- サンプルプログラム:複素数

- 行列計算

- 【演習】

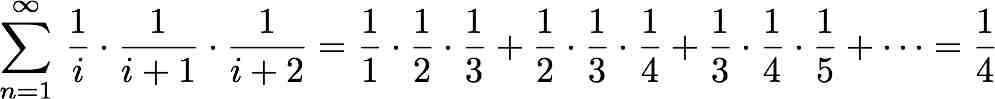

- サンプルプログラム: 級数

- 【演習】

- 部分配列

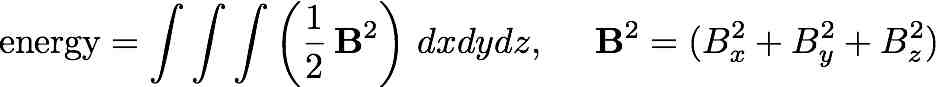

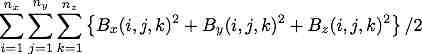

- サンプルプログラム: 3次元ベクトル場の全エネルギー

- ソースコードの書き方

- 予約語

- 【演習】

- コメント行の書き方

- 【演習】

- 定数

- 【演習】

- 数値演算

- 【演習】

- 倍精度浮動小数点数の指定方法

- 【演習】

- 【演習】

- 数字表現

- 型名

- 構造体 (derived type)

- 【演習】

- 【演習】

- 宣言

- 暗黙の型宣言

- 暗黙の型宣言はなぜバグが入りやすいか

- 【演習】

- 【演習】

- 行の継続

- セミコロン

- 1次元配列

- 【演習】

- 2次元配列

- メモリ空間中での2次元配列の各要素の位置

- 3次元配列

- if構文

- 論理式

- 論理値

- case 構文

- 【演習】

- 【演習】

- 繰り返し構文(doループ)

- 【演習】

- exitとcycle

- 【演習】

- 関数

- 【演習】

- サブルーチン

- 値渡しと参照渡し

- 【演習】

- 入出力属性

- 【演習】

- 入出力属性の種類

担当教員 †

陰山 聡

演習日 †

- 2010.05.06

- 2010.05.13

はじめに †

特徴 †

C言語との差分に注目したFortran90/95言語の入門

目標 †

この「計算科学演習I」で扱うFotranソースコードが自由に読めること。 Fortran90/95の特性を活かした綺麗なコードが自由に書けること。

エディタとコンパイラ †

- Emacsのmajorモードをf90に設定すると便利(f95モードは用意されていない)

- ミニバッファでf90-modeと打つ (Esc-x f90-mode)

- tabキーでソースコード(現在行)を整形。

- tabキーで適切なend構文を自動入力。

- ^jで整形改行

- scalar上でのコンパイルコマンドは pgf95 またはpgf90

- フリーのFortran95コンパイラ

- gfortran (gnu Fortran): http://gcc.gnu.org/fortran/

- g95: http://www.g95.org/

Fortran90/95の歴史 †

- FORTRAN(全部大文字の)という言語は存在しない。

- Fortran90やFortran95という言語ならある。

- FORTRAN66。

- 1966年に標準化。

- FORTRAN77

- 1977年に標準化。

- if/then/else

- 広まった

- Fortran90

- 1991年に標準化。

- 大幅な改訂

- Fortran95

- F90からのマイナーバージョンアップ

Fortran90はFORTRAN77とは大きく違う。違う言語と考えるべき。

| f95 - f90 | << | f90 - f77 |

なぜFortran90/95か? †

- 計算速度が速い

- スーパーコンピューティングは速さが命。

- C/C++でもFortranと同じくらい速いコードは書けるが、遅いコードも書けてしまう。

- 言語としての自由度が高いために、コンパイラが困る。最適化ができなくなる。

- 便利

- 道具(言語)は目的にあったものを

- 数学的計算にはFortran90/Fotran95が適している

- For-mula Tran-slator

- 数値計算ライブラリの抱負な蓄積。

Fortran Legacy †

LegacyなコードはFortranの財産 †

Legacyな人間は負の遺産。 †

『FORTRAN77に何の不満もない。これでxx年やってきた。』

・・・時代に33年(2010-1977)遅れている。

定番、hello, world プログラム †

K&Rに出てくるC言語でのhello, worldプログラムは、

#include <stdio.h>

main () {

printf("hello, world.\n");

}

である。

Fortran90/95ではこうなる。

program hello_world implicit none print *, "hello, world." end program hello_world

このようにほとんど同じである。 いくつかの細かい違いは、

- Fortran90/95ではmainプログラムは program nameとして宣言する。nameは任意。

- implicit noneの意味は後述。

- Fortran90/95では標準入出力機能は言語に組み込まれている(ヘッダファイルをインクルードする必要はない(そもそもヘッダファイルというものがない))。

- Fortran90/95では print *で標準出力へ。

- 行末にセミコロン不要。

- 文字列はダブルクォーテーションマーク(")で囲む。(C言語と同じ)

- シングルクウォーテーションマーク(')でも同じ意味。(これはC言語と違う)

【演習】 †

計算機「scalar」 で、上のFortran90/95プログラムをエディタで入力し、 ファイル名hello_world.f95として保存せよ。

- ls -l コマンドでファイルを確認せよ。

- hello_world.f95 をコンパイルせよ。

- pgf95 hello_world.f95

- 実行せよ。

- ./a.out

そのプログラム(hello_world.f95)のメッセージ("hello, world.")を自由に変え、 コンパイル&実行せよ。

サンプルコードによるFortran90/95入門 †

まずはC言語の復習も兼ねて、線形合同法による乱数生成プログラムのC言語版を見てみよう。

C言語版 †

/*

* random number by

* the linear congruential generator (lcg):

*

* n_new = (n_old*A+C) % M

*

*/

#include <stdio.h>

#define A 109

#define C 1021

#define M 32768 /* = 2^15 */

int lcg_n = 10; /* initial value */

double random_0_to_1(void)

{

lcg_n = (lcg_n*A+C) % M;

return (double)lcg_n / (M-1);

}

main(void)

{

int i;

int loop_max = 100;

int n = 10; // initial condition

for (i=0; i<loop_max; i++) {

printf("%d %f\n",i, random_0_to_1());

}

}

Fortran90/95版 †

次にFortran90/95言語で同じことをするコードを見てみよう。

!

! random number by

! the linear congruential generator (lcg):

!

! n_new = mod(n_old*A+C,M)

!

! by Akira Kageyama, Kobe Univ.

! on 2010.05.05.

!

module lcg

implicit none

integer, parameter :: SP = kind(1.0)

integer, parameter :: DP = selected_real_kind(2*precision(1.0_SP))

integer, parameter :: A = 109

integer, parameter :: C = 1021

integer, parameter :: M = 2**15

integer :: lcg_n = 10 ! initial value

contains

function random_0_to_1()

real(DP) :: raondom_0_to_1

lcg_n = mod(lcg_n*A+C,M)

random_0_to_1 = real(lcg_n,DP) / (M-1)

end function random_0_to_1

end module lcg

program random_number

use lcg

implicit none

integer :: i

integer :: loop_max = 100

do i = 1 , loop_max

print *,i, random_0_to_1()

end do

end program random_number

moduleはデータと関数をひとまとめにしたもの。 C++やJavaのclassに対応。

【演習】 †

上のFortran90/95プログラムをrandom_number.f95という名前のファイルに保存し、 コンパイル&実行せよ。

Fortran90/95に対する誤解 †

以下全てFORTRAN66/77と誤解している。

- 変数名は6文字までなんでしょう?・・・そんなことはありません。

- ソースコードは全部大文字で書くんでしょう?・・・それも可能ですが、わざわざそんな読みにくいことをする必要はありません。

- ソースコードは固定形式(7列目から72列目まで)なんでしょう?・・・そんなことはありません。

- 構造体がないんでしょう?・・・あります。よく使います。

- ポインタがないんでしょう?・・・あります。あまり使う必要はありませんが。

- 演算子を自分で定義することができなんでしょう?・・・できます。よく使います。

- 関数や演算子の多重定義ができなんでしょう?・・・できます。よく使います。

- 再帰呼び出しができなんでしょう?・・・できます。あまり使いませんが。

- 関数とデータをまとめてひとかたまりにする(クラス化する)ことなんてできないんでしょう?・・・できます。よく使います。上のサンプルプログラムで使ったmoduleがそれです。

- 情報の隠蔽(カプセル化)ができないんでしょう?・・・できます。よく使います。

実際的なサンプルコード †

上の最後に述べた情報隠蔽(カプセル化)は名前空間を分離し、 バグの入りにくいコードを書くためには不可欠な機能である。 上のサンプルプログラムにカプセル化を施したコードを下に示す。 冒頭近くに3行ほど追加しただけである。 諸君は既にJavaを知っているから、この3行の意味は明白であろう。

!

! random number by

! the linear congruential generator (lcg):

!

! n_new = mod(n_old*A+C,M)

!

! by Akira Kageyama, Kobe Univ.

! on 2010.05.05.

!

module lcg

implicit none

private ! default

public :: SP, DP ! constants

public :: random_0_to_1 ! function

integer, parameter :: SP = kind(1.0)

integer, parameter :: DP = selected_real_kind(2*precision(1.0_SP))

integer, parameter :: A = 109

integer, parameter :: C = 1021

integer, parameter :: M = 2**15

integer :: lcg_n = 10 ! initial value

contains

function random_0_to_1()

real(DP) :: random_0_to_1

lcg_n = mod(lcg_n*A+C,M)

random_0_to_1 = real(lcg_n,DP) / (M-1)

end function random_0_to_1

end module lcg

program random_number_capsule

use lcg

implicit none

integer :: i

integer :: loop_max = 100

do i = 1 , loop_max

print *,i, random_0_to_1()

end do

end program random_number_capsule

Fortran90/95の特徴 †

数値演算や計算機シミュレーションに適した言語である。 特にスーパーコンピュータ向けの言語としては最適。 オブジェクト指向プログラミングや並列計算機への対応も意識された言語である。

- これらの意味を納得できるようになることが目標。

C言語と極端に差がつく例 †

部屋の中の温度場の分布から平均気温を求めよう。 温度場を3次元float配列 f(nx,ny,nz)で表す。3つの整数nx, ny, nzは実行時まで不定とする。 平均気温を求めるには、 全ての格子点(i,j,k)上でのfの値を足して格子点の総数で割ればよいものとする。

任意サイズの3次元単精度実数(浮動小数点数)配列を受け取り、 その平均値を返す関数を作ろう。

Fortran90/95ではこう書ける。 †

このようにわずか4行で書ける。

real function mean_value(f) real, dimension(:,:,:) :: f mean_value = sum(f) / (size(f,1)*size(f,2)*size(f,3)) end function mean_value

このプログラムの意味は後で説明するが、 ここに出てくるsumやsizeはライブラリではなく組み込み関数、 つまりFortran90/95言語にもともと含まれている関数である。

【演習】 †

上の関数をC言語で作れ。

- scalar上でのCコンパイラはcc, gccである。

サンプルプログラム:複素数 †

をFortran95で書くと、

complex :: i = (0.0,1.0) real :: pi = 3.141593 print *,' exp(i*pi) = ', exp(i*pi)

行列計算 †

行列のかけ算のためにFortran90/95ではmatmulという組み込み関数が用意されている。 また、行列の転置をとる組み込み関数transposeも用意されている。 したがって、行列A(例えば10行10列の2次元配列)の転置と別の行列Bの積を計算しそれを行列Cとする計算、つまり

をFortran90/95で書くと、

real, dimension(10,10) :: A, B, C C = matmul(transpose(A),B)

と一行で書ける。

行列の足し算も簡単である。 上の式の右辺に別の行列Dを加える演算はそのまま

C = matmul(transpose(A),B) + D

と書けばよい。

【演習】 †

以下のプログラムをmatmul_a_transpose_b.f95というファイルに保存し、 コンパイル&実行せよ。

program matmul_a_transpose_b implicit none real, dimension(10,10) :: A, B, C, D A = 1.0 ! A(i,j) = 1 for all i and j. B = 2.0 ! B(i,j) = 2 D = 3.0 ! D(i,j) = 3 C = matmul(transpose(A),B) + D print *, 'max element of C is ', maxval(C) end program matmul_a_transpose_b

サンプルプログラム: 級数 †

級数

の最初の1000項の和を求めるプログラムも、式をそのまま書けばいい。まさにFormula Translation。

program series_one_forth

implicit none

integer, parameter :: nterms = 1000

real, dimension(nterms) :: x, y, z

integer :: i

do i = 1 , nterms

x(i) = 1.0 / i

y(i) = 1.0 / (i+1)

z(i) = 1.0 / (i+2)

end do

print *,'ans = ', sum(x*y*z)

end program series_one_forth

【演習】 †

上のプログラムを series_one_forth.f95という名前に保存し、 コンパイル&実行せよ。

部分配列 †

上の例では第1行目から第1000項目までの和をとっていた。 もしも第50項目から第90行目までの和が欲しければ以下のようにすればよい。

program series_one_forth_02

implicit none

integer, parameter :: nterms = 1000

real, dimension(nterms) :: x, y, z

integer :: i

do i = 1 , nterms

x(i) = 1.0 / i

y(i) = 1.0 / (i+1)

z(i) = 1.0 / (i+2)

end do

print *,'ans02 = ', sum(x(50:90)*y(50:90)*z(50:90))

end program series_one_forth_02

ここに出てきた x(50:90)などは部分配列と呼ぶ。 部分配列も含めてFortran90/95には配列を扱うための便利な機能が多数用意されている。 配列機能については次回詳しく解説する。

サンプルプログラム: 3次元ベクトル場の全エネルギー †

空間中に分布する磁場(3成分ベクトル場)の全磁気エネルギーは

で与えられる。 計算機シミュレーションコードでこの磁場が 3次元配列 Bx(nx,ny,nz), By(nx,ny,nz), Bz(nx,ny,nz) で書かれているとき、 空間の体積が1に規格化されているとして、エネルギーは

と書ける。この量を計算して出力するFortran90/95コードは、

print *,' energy = ', sum(Bx**2+By**2+Bz**2)/2

とわずか1行(定義式そのもの)を書けばよい。 配列のサイズ(nx,ny,nz)が実行時まで不定でもよい。

ソースコードの書き方 †

大文字・小文字 †

- Fortran90/95のソースコードではアルファベットの大文字と小文字は区別しない。

- kobe と Kobe と KOBE は同じ

- 文字列変数の中では当然区別される。

自由形式。C言語とほぼ一緒。 †

- 1行は132文字まで

予約語 †

Fortran90/95には予約語が存在しない。 ユーザ定義の変数名であればコンパイラが賢く判断してくれる。 一方、C言語には32個も予約語がある。 C99ではさらに5個増えた。

たとえば・・・ 次のCプログラムはコンパイルエラーになる。

main()

{

int dee, daa, doo;

int de, da, do;

dee = de*de;

}

【演習】 †

下のプログラムをreserved_words.f95というファイルに保存し、 予約語がないことを確認せよ。

program reserved_words implicit none integer :: id=2, ie=3 integer :: if if ( id==ie ) if=0 end program reserved_words

コメント行の書き方 †

C言語では

/* この間がコメント */

である。(C99では // から行末までもコメントとなった。)

Fortran90/95では

! 一行の中でこの文字以降がコメント( C99やC++、JAVAの//と同じ)

【演習】 †

これまでに作ったプログラムに自由にコメントを入れよ。

定数 †

C言語ではプリプロセッサを使って

#define NX 100

とするが、

Fortran90/95ではC++のconstと同様

integer, parameter :: NX = 100

と書ける。コンパイラが型チェックをしてくれるのでバグが入りにくい。

【演習】 †

上で書いたseries_one_forth.f95の定数ntermsを設定(integer, parameter nterms=100)した後に、 変更(nterms=200など)するとエラーになることを確認せよ。

数値演算 †

四則演算はC言語と同じ

a+b, a-b, a*b, a/b

優先順位も同じ。

Fortran90/95でのべき乗は

a**b

余りは(C言語ではa % b)はFortran90/95では、

mod(a,b)

【演習】 †

以下のプログラムをelemental_operators.f95に保存して、 コンパイル&実行せよ。

program elemental_operators implicit none real, parameter :: pi = 3.141593 complex :: z print *, ' pi = ', pi print *, ' pi+pi = ', pi+pi print *, ' pi-pi = ', pi-pi print *, ' pi*pi = ', pi*pi print *, ' pi/pi = ', pi/pi print *, 'pi**pi = ', pi**pi z = (pi,pi) print *,' z = ', z print *,' z*pi = ', z**pi print *,' z**z = ', z**z end program elemental_operators

倍精度浮動小数点数の指定方法 †

kindパラメータ †

計算科学では実数の物理量を数値的に表現するのに単精度ではなく、 倍精度の浮動小数点数を使うのが普通である。 (単精度実数では精度が不十分なため。)

まは、スーパーコンピュータは単精度浮動小数点ではなく、 倍精度浮動小数点数の演算(四則演算)を高速に処理できるよう設計されている。 従ってFortran90/95言語での倍精度浮動小数点数の表現方法に早めに慣れておくことは重要である。

Fortran90/95で倍精度浮動小数点数を表す方法は幾つかある。 最も簡単でportabilityの高い方法は以下の方法であろう。 まず、単精度浮動小数点数の精度に関係したある整数定数を定義する。 ここではその整数をSPという名前にする。 SPとはSingle Precision(単精度)の頭文字をとったものである。

integer, parameter :: SP = kind(1.0)

次に、このSPを使って単精度として指定した浮動小数点数の2倍の精度を持つ浮動小数点数、 つまり倍精度浮動小数点数に関係したある整数定数(ここではDPという名前)を以下のようにして定義する。

integer, parameter :: DP = selected_real_kind(2*precision(1.0_SP))

この整数定数DPはDouble Precisionを意味する。

こうして定義した二つの整数SPとDPを使って単精度浮動小数点や倍精度浮動小数点数を宣言する。

real(kind=SP) :: a real(kind=DP) :: b

とすると、aは単精度浮動小数点、bは倍精度浮動小数点数である。

上のプログラムのkind=の部分は省略可能である。 つまり

real(SP) :: a real(DP) :: b

としてもよい。

数値データの精度指定にもこのSPやDPを使う。

a = 1.0_SP ! 単精度の1.0 b = 1.0_DP ! 倍精度の1.0

サンプルプログラムを見てみよう。

program double_precision_real implicit none integer, parameter :: SP = kind(1.0) integer, parameter :: DP = selected_real_kind(2*precision(1.0_SP)) real(SP) :: a real(DP) :: b a = 3.1415926535897323846264338327950288_SP b = 3.1415926535897323846264338327950288_DP print *,' a, b = ', a, b end program double_precision_real

【演習】 †

上のプログラムをdouble_precision_real.f95という名前のファイルに保存し、 コンパイル&実行せよ。

【演習】 †

double_precision_real.f95に現れる二つのkindパラメータSPとDPには実際にはどんな値が入っているか調べよ。

数字表現 †

- 浮動小数点数

- 1. ! デフォルト精度

- 0.1_SP ! kindパラメタSPの浮動小数点数

- 3.141593_DP ! kindパラメタDPの浮動小数点数

- 0.31415926535897932e-1_DP ! 上に同じ

型名 †

| 型 | C ( C99 ) | Fortran90/95 | 補註 |

| 文字 | char | character | |

| 文字列 | char[n+1] | character(len=n) | nは文字長 |

| 整数 | int | integer | integer(kind=4)でも可 |

| 実数 | float | real | real(kind=SP)でも可 |

| 倍精度実数 | double | real(kind=DP) | |

| 「長い」整数 | long | integer(kind=8でも可) | kindの整数はシステム依存 |

| bool | ( _Bool ) | logical | 値は .true. または .false. |

| 複素数 | ( _Complex ) | complex | |

| 構造体 | struct | type | 詳しくは後述 |

構造体 (derived type) †

C言語の構造体とほとんど同じである。下の例をみよ。

program type

implicit none

type student

character(len=20) :: first_name, last_name

integer :: age

end type student

type(student) :: st

st = student("Albert", "Einsten", 19)

print *,st%first_name, st%last_name, st%age

end program type

構造体のメンバにアクセスするのに%を使う。

【演習】 †

上のプログラムをtype.f90に保存し、コンパイル&実行せよ。

【演習】 †

student型の構造体変数をもう一つ(例えばst2という名前)を作り、 stのデータをst2にコピーせよ。

宣言 †

C言語では変数の宣言はブロックの先頭にまとめて置く。(C99やC++はもっと自由だが。) Fortran90/95でも同じ。

暗黙の型宣言 †

Fortran90/95ではimplicit noneを省略すると「暗黙の型宣言」をしたことになる。 暗黙の型宣言とは、次の6つのアルファベット i,j,k,l,m,n で始まる変数は整数である等のルールである。 バグが入りやすいので、暗黙の型宣言は使わない方が良い。 Fortran90/95プログラムでは常にimplicit none宣言をすること。

暗黙の型宣言はなぜバグが入りやすいか †

宣言したつもりのない変数を間違って使っていても気がつかない可能性がある。 例えば、次のプログラムにはバグがある。すぐに見つけられるか?

program use_implicit_none integer :: fresh_meat flesh_meat = 100 ! yen print *, "today's price = ", fresh_meat end program use_implicit_none

【演習】 †

上のプログラムをuse_implicit_nene.f95というファイルに書き込み、コンパイル&実行せよ。

- バグがあるのにコンパイラは教えてくれないだけでなく、 何事もないかのように正常終了する。しかも、それらしい答えを返す。 バグがあることに気がつかない!

【演習】 †

今作ったuse_implicit_nene.f95の2行目(program ...の次の行)に implicit noneと書いてから、コンパイルせよ。

行の継続 †

行末に&をつけると継続行

a = b + c + &

d + f

セミコロン †

セミコロンは改行と同じ

tmp = right right = left left = tmp

と

tmp = right; right = left; left = tmp

は同じ。

1次元配列 †

C言語では

array01[NX];

が大きさNXの1次元配列である。 メモリ上に、array01[0], array01[1], array01[2], ..., array01[NX-1]と並んでいる。

Fortran90/95では

integer, dimension(NX) :: array01

と宣言するとメモリ上に、array01(1), array01(2), array01(3), ..., array01(NX)と並ぶ。 配列のインデックスは1から始まる。

【演習】 †

大きさNXの1次元整数配列array_01を作り、 各要素に1,2,3,...,NXを代入した上で、 全要素の和をとるFortran90/95プログラムを書け。

2次元配列 †

厳密に言えばC言語では2次元配列はない。 あるのは「配列の配列」である。 つまり二つの整数インデックスiとjを使って

array02[j][i]

という形でアクセスできるものである。

このarray02を2次元配列とは呼べないということは、 array02のサイズ(インデックスiとjの範囲)は実行時に不定として、 array02をまるごと引数で受け取る関数がC言語では作れないことを考えれば納得出来るであろう。

メモリ空間中での2次元配列の各要素の位置 †

上記のarray02は、

array02[0][0], array02[0][1], array02[0][2], ..., array02[0][NX-1]

と並び、そして (それに続く場合もあるし、 まったく別の場所にあるかもしれない)ある位置から、

array02[1][1], array02[1][1], array02[1][2], ..., array02[1][NX-1]

という順番で並ぶ。

一方、 Fortran90/95ではarray02(i,j)という形でアクセスできる量は本物の2次元配列である。 サイズがわかっている場合には

integer, dimension(NX,NY) :: array02

と宣言する。 不明の場合には、

integer, dimension(:,:) :: array02

と宣言し、後ほど(実行時に)メモリをallocateする。 メモリ上では、array02の要素は

array02(1,1), array02(2,1), array02(3,1), ..., array02(NX,1), array02(1,2),...

に全ての要素(NX*NY個)が連続して並ぶ。

配列の要素がメモリ空間中に連続してあることは、 メモリへのアクセス速度が極めて重要となるスーパーコンピューティングでは極めて重要である。

3次元配列 †

C言語では

array03[k][j][i]

が上の意味での「擬似」3次元配列である。

Fortran90/95では

array03[i][j][k]

が3次元配列で、 宣言は

integer, dimension(NX,NY,NZ) :: array03

または

integer, dimension(:,:,:) :: array03

とする。

if構文 †

if文はC言語と似ている。下の例を見れば一目瞭然であろう。

if (criterion) then action end if

actionが1行で書けるなら

if ( criteron ) action

ともできる。

else-if構文も簡単である。

if (criterion_1) then action_1 else if (criterion_2 ) then action_2 else if (criterion_3 ) then action_3 end if

論理式 †

これも下の例を見ればわかるであろう。

if (a==b) then ! aとbが等しい if (a>b) then if (a>=b) then if (a<b) then if (a<=b) then if (a/=b) then ! aとbが等しくない

論理値 †

bool変数はlogicalという型名を持ち、

.true.

か

.false.

の二つをとる。

logical :: a, b, c a = .true. b = .false. c = a .and. b c = a .or. b

case 構文 †

C言語でいうswitch文である。

select case (case expression) case (case selector 1) action 1 case (case selector 2) action 2 case (case selector 3) action 3 . . case default ! なくても良い。 default action end select

C言語では普通breakが必要だがFortran90/95のcase文には不要である。

【演習】 †

次のプログラムをcase.f95に保存し、実行せよ。

program case

implicit none

integer :: month

month = 6

select case (month)

case (1)

print *,'January.'

case (2)

print *,'February'

case (3:5)

print *,'Spring'

case default

print *,'Other than spring.'

end select

end program case

【演習】 †

後述するが、Fortran90/95は文字列の取り扱いがC言語よりもずっと簡単である。 例えば、長さの違う文字列をselect case構文で簡単に場合分けできる。

program case_string

implicit none

character(len=*), parameter :: color = 'white'

select case (color)

case ('aka')

print *, 'red'

case ('ao')

print *, 'blue'

case ('midori')

print *, 'green'

case default

print *, "I don't know the color."

end select

end program case_string

繰り返し構文(doループ) †

C言語でいうfor文である。

incrementが1の場合のdo-loop †

program do_loop

implicit none

integer :: i

do i = 1 , 100

print *, ' i = ', i

end do

end program do_loop

incrementが1以外の場合のdo-loop †

program do_loop

implicit none

integer :: i

do i = 1 , 100 , 2

print *, ' i = ', i

end do

end program do_loop

【演習】 †

- 上のプログラムをdo_loop.f95に保存し、increment値(上の場合2)を変えて実行せよ。

- do_loop.f95のdo文を

do i = 100 , -100 , -2

として実行せよ。

exitとcycle †

整数のカウンターのないdo-loopも可能である。

do ... end do

このままだと無限ループになるので、通常はある条件を満たせばループから抜け出すようにする。

C言語だとbreak文でループから抜け出す。(正確には最も内側のループから抜け出す。) Fortran90/95でbreakに相当するのはexitである。

do

...

if (condition) exit !---+

end do ! | ループから抜け出す。

!<--+

C言語ではループの先頭に戻る時にはcontinue文を使うが、 それに相当するのはFortran90/95ではcycleである。

do !<--+ ... ! | 戻る if (condition) cycle !---+ ... end do

【演習】 †

if文、select case文、do文を使って自由にプログラムを作ってみよ。

関数 †

C言語と同様に関数(function)という手続き(procedure)は、 Fortran90/95プログラムの重要な構成部品である。 関数の使い方は以下の例を見ればわかるであろう。

【演習】 †

- 次のプログラムをfunction01.f95として保存し、実行せよ。

integer function next_int(i) implicit none integer, intent(in) :: i next_int = i+1 end function next_int program function01 implicit none integer, external :: next_int print *, 'ans = ', next_int(-100) end program function01

intent(in)は引数iが入力引数であり、関数next_intの内部で変更されることがないことを保証するものである。 - 関数を以下のように内部副プログラムとしてメインの中に含むこともできる。

次のプログラムをfunction02.f95として保存し、実行せよ。

program function02 implicit none print *, 'ans = ', next_int(-100) contains integer function next_int(i) integer, intent(in) :: i next_int = i+1 end function next_int end program function02

サブルーチン †

関数の本来の機能は入力に応じて出力を返すものであるが、 出力(返り値)が不要な場合も多い。 C言語ではvoid関数とするこのような関数を Fortran90/95ではsubroutineと呼ぶ。

サブルーチンを呼び出すにはcall subroutine名とする。 以下の例をみよ。

subroutine next_int(input, output) implicit none integer, intent(in) :: input integer, intent(out) :: output output = input + 1 end subroutine next_int program subroutine01 implicit none integer :: i, j i = 10 call next_int(i,j) print *, 'ans = ', j end program subroutine01

値渡しと参照渡し †

C言語は値渡し、Fortran90/95は参照渡しである。 C言語が値渡しであることは、以下の例でkの値が変わっていないことから確認できる。

void pass(int i)

{

i = 0;

printf("i=%d\n", i);

}

main()

{

int k = 2010;

printf("before: k = %d\n", k);

pass(k);

printf("after: k = %d\n", k);

}

これと似たプログラム(同じではない)をFortran90/95で書くと以下のようになる。

subroutine pass(i) implicit none integer :: i i = 0; print *, "i=", i end subroutine pass program call_by_reference implicit none integer :: k = 2010 print *, "before: k = ", k call pass(k) print *, "after: k = ", k end program call_by_reference

このプログラムではkの値はサブルーチンpassを読んだ後に変更されている。

【演習】 †

上の二つのプログラムをそれぞれcall_by_value.c、call_by_reference.f95という名前で保存し、実行せよ。

入出力属性 †

値渡しに比べて参照渡しは値をコピーする必要がないので速い。 従って計算速度を重視するFortran90/95言語では値渡しを採用していないのは当然である。 だが、上のcall_by_reference.f95プログラムで見たように、 引数として渡した変数がそのサブルーチン内部で勝手に(誤って)変更されると見つけにくいバグになり、危険である。 このような事故を防ぐためにFortran90/95には引数に入出力属性をつけることができる。 サブルーチンincrementの引数iは入力属性をもつと指定すると(下のプログラムの2行目)、 コンパイラがエラーを出してくれる。

subroutine increment(i) ! コンパイルエラーを出してくれる integer, intent(in) :: i i = 0; print *, "i=", i end subroutine increment program call_by_reference implicit none integer :: k = 2010 print *, "before: k = ", k call increment(k) print *, "after: k = ", k end program call_by_reference

【演習】 †

call_by_reference.f95を上のように変更してコンパイルせよ。

入出力属性の種類 †

入出力属性には以下の3種類がある。

| intent(in) | 入力 | その手続き内で値は変更されない変数 |

| intent(out) | 出力 | その手続き内で値が設定される変数 |

| intent(inout) | 入出力 | 両者の混合。デフォルト。 |

バグの混入を防ぐために、Fortran90/95プログラムではすべての引数に入出力属性をつけることを強く勧める。

as of 2025-08-23 (土) 04:25:13 (222)